In case you’re just catching up, COP is an international climate meeting held each year by the United Nations. The name stands for “Conference of the Parties,” meaning those countries who have joined the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Parties to the treaty have committed to take voluntary actions to prevent “dangerous anthropogenic [human-caused] interference with the climate system.”

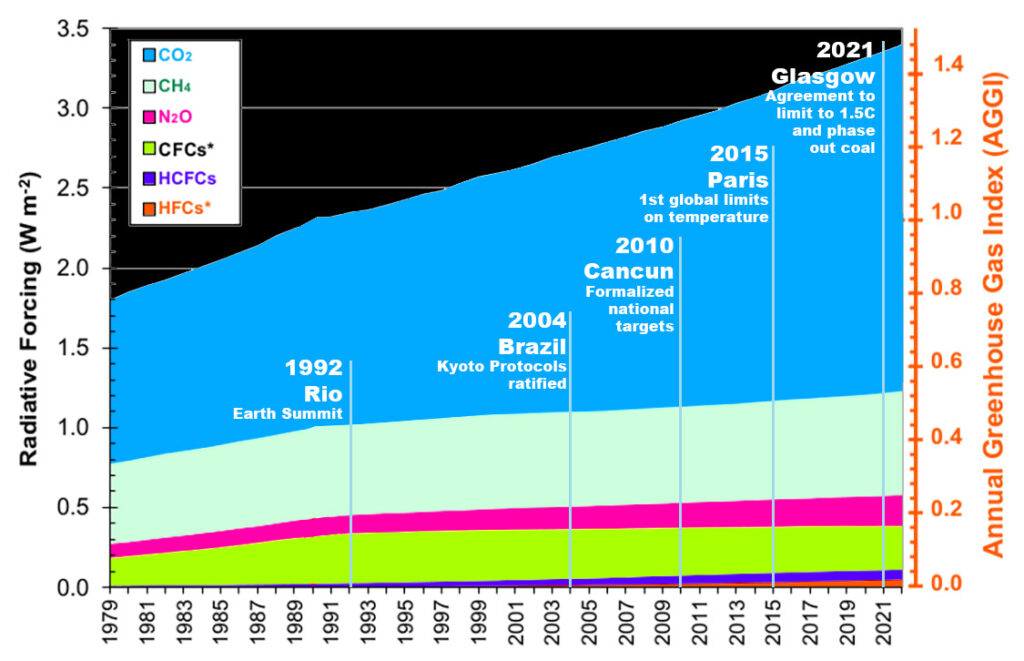

Perhaps the most important word in that description is “voluntary”. At the 1997 Kyoto conference, for the first time, a target was set for reducing greenhouse gas emissions: the aim was to bring them down by about 5%, compared with 1990 levels, by 2012. Yet global greenhouse gas emissions have been increasing every year since then.

COP28, the 28th annual United Nations (UN) climate meeting taking place this week, is being held in Dubai in the UAE, one of the world’s top 10 oil-producing nations. Sultan al-Jaber, appointed president of COP28, is the chief executive of the state-owned oil company, which reportedly plans to expand production capacity.

The BBC has obtained documents that suggest the UAE planned to use its role as host to strike oil and gas deals with countries attending the conference.

Meanwhile, President Biden will not attend the climate talks. The president responsible for the greatest investment in US history in a clean energy transition has also presided as U.S. oil and natural gas production have set new records. And the official US stance is “ending emissions”, not “ending fossil fuels”; which means counting on carbon capture technology, which despite numerous attempts, to date has never been shown to work at scale.

In spite of COP’s legacy of broken promises, that’s not to say that no good comes out of it; although the good news is somehow always mixed. For example, a longtime sticking point has been the proposal that the wealthier (and heaviest emitting) countries should contribute to a fund to pay for damage from climate-driven storms and drought ravaging poorer countries. In a surprise that has brought an ovation to the floor of COP28’s first day, the fund was actually launched and received contributions from the EU, UK, US and others totaling around $400 million. That sounds promising, but the details reveal that the US contribution is a paltry $17 million, a far cry from the Biden administration’s pledge to provide $11.4 billion per year by 2024. And this should be put in the context of where real money goes: military aid from the US to other countries dwarfs that number, and Qatar has reportedly spent $220 billion alone to host the 2022 World Cup.

Getting nearly every nation on the planet to agree to work together to stop global warming is a slow and difficult process. A pact to actually phase out fossil fuels might be within reach, but it’s likely to take years, if not decades, to reach that on a global scale.

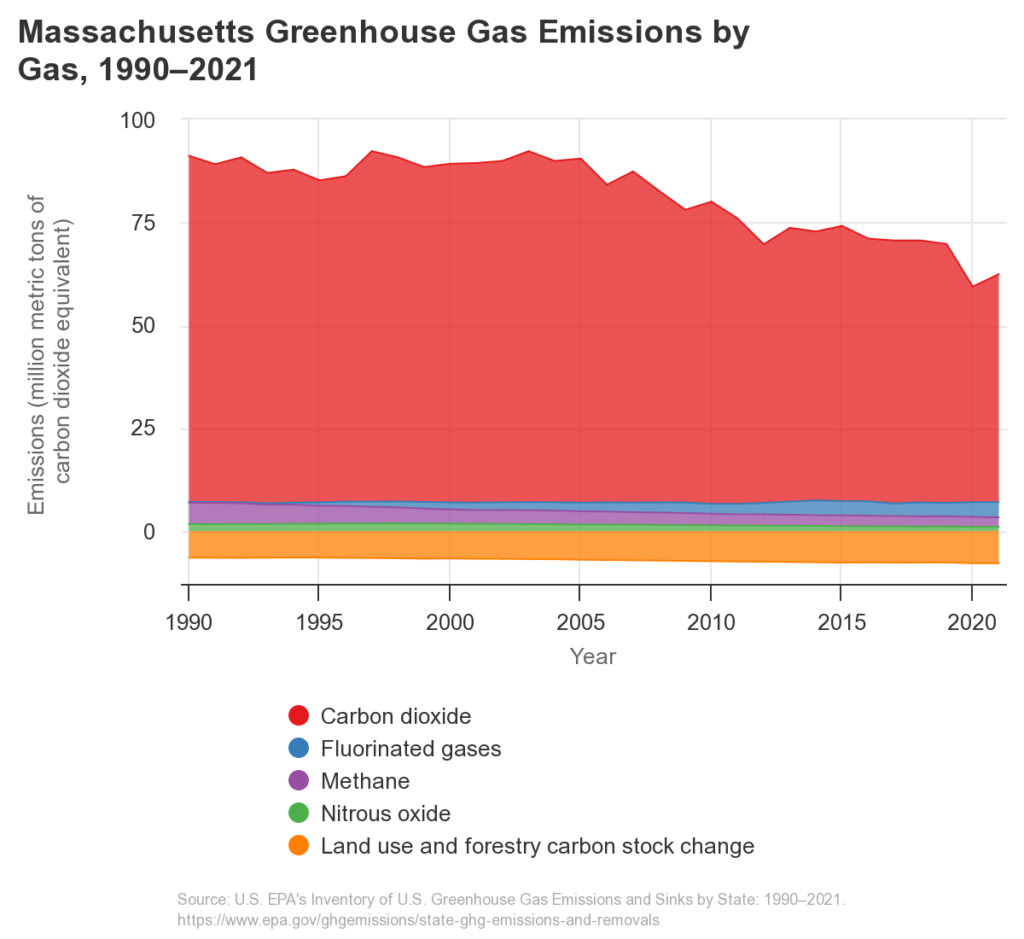

So where does that leave us? Global agreements are of course crucial for the long term, but what we can see is that the real progress is being made on the local level. No Fracked Gas in Mass and our partners across Massachusetts have helped put a real dent in greenhouse gas emissions in this state and our momentum is continues to build, shutting down Peaker plants and other fossil fuel infrastructure while working to press our state government, its agencies and legislature to abide by the Global Warming Solutions Act. Is it working? Take a look at the following chart of greenhouse gas emissions in Massachusetts over the period since the Kyoto Agreement and compare it to the global chart at the top!