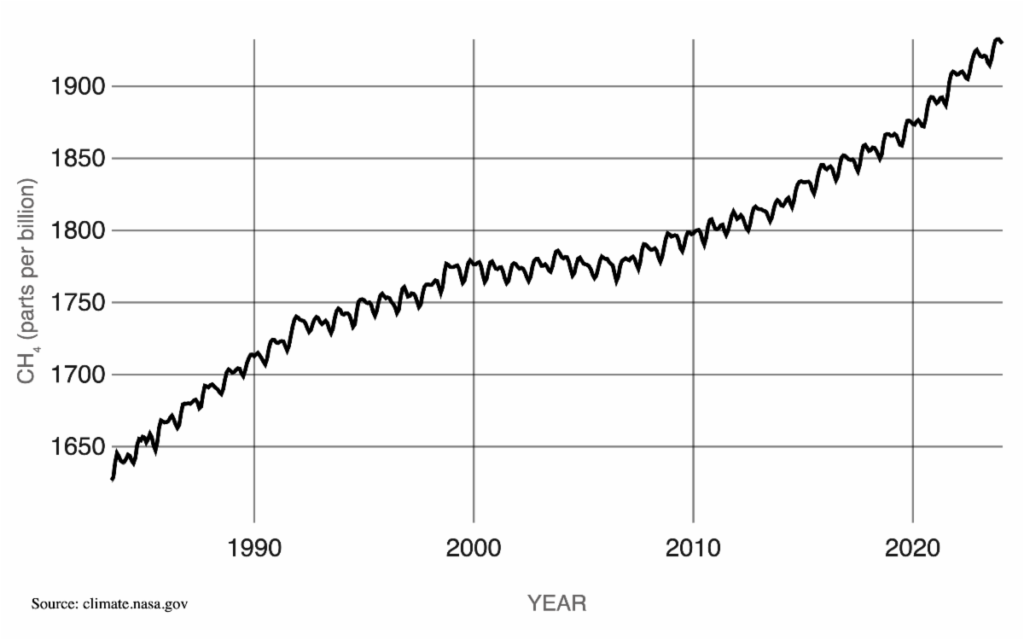

The concentration of methane (CH4) in the atmosphere has more than doubled over the past 200 years. Methane is a potent greenhouse gas that has caused around 30% of all human-caused global warming since the start of the Industrial Revolution in the late 1700s. Most methane emissions are anthropogenic; that is, they are the result of human activity – including from the fossil fuel industry, landfill sites and agriculture.

However, about 40% of methane emissions are from natural sources. In fact, wetlands are the world’s largest natural source of methane emissions. Wetlands occur in many different forms, including Arctic permafrost peatlands, tropical mangrove plantations, and salt marshes. Although wetlands are natural carbon sinks, they also release methane, mainly from rotting vegetation.

Now, the rise in global temperatures and disruptions in rainfall patterns due to climate change are causing wetlands to release methane far more rapidly than historical norms. This is known as a “wetland methane feedback” loop.

According to a recent report from PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academies of Science), “The degree to which future expansion of wetlands and CH4 [methane] emissions will evolve and consequently drive climate feedbacks is thus a question of major concern… We find that climate change-induced increases in boreal wetland extent and temperature-driven increases in tropical CH4 emissions will dominate anthropogenic CH4 emissions by 38 to 56% toward the end of the 21st century.”

Wetland methane emissions surges have been evident in the tropics first, but as the permafrost melts in the Arctic that region is also contributing methane to the atmosphere. The world’s permafrost has almost three times as much carbon as is currently in the atmosphere, locked up areas such as the upland Yedoma Taliks in northern Siberia. As the permafrost thaws, it’s likely that methane emissions will increase as microbes break down organic material.

In this century, methane emissions from wetlands have risen even faster than in the most pessimistic climate projections. Most of the climate models that are used as a basis for the reports that the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) relies on to assess the state of global climate change don’t account for the wetland methane feedback loop. The assumption has generally been that methane emissions from natural sources will remain relatively stable going forward. However, according to Dr. Mark Lunt (quoted in Carbon Brief), “committed emissions from a wetland-climate methane feedback have the potential to offset any reductions made through agreements like the Global Methane Pledge.”

A study from Nature Climate Change reported the observations from 167 sites in northern wetlands to assess the release of carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide emissions due to atmospheric warming. They showed that the 100-year global warming potential of wetlands increased by 57% in response to an average temperature increase of 1.5–2.0 °C. Their results show that “warming undermines the mitigation potential of pristine wetlands even for a limited temperature increase of 1.5–2.0 °C, the main goal of the Paris Agreement.”

What all this means is that anthropogenic emissions must be decreased by even more than current climate agreements call for in order to offset the rise in natural emissions levels as the planet warms. Environmentalists, we have our work cut out for us!

References:

PNAS: Emerging role of wetland methane emissions in driving 21st century climate change

Carbon Brief: ‘Exceptional’ surge in methane emissions from wetlands worries scientists

Inside Climate News: Surging Methane Emissions Could Be a Sign of a Major Climate Shift

NASA Climate: Methane