Our electrical grid is the system of power generation facilities and transmission lines that provide the power that keeps the lights on throughout the country. In order for these facilities to connect to the grid to supply energy, they must navigate a complex regulatory environment to file a request to join the interconnection queue.

What is an interconnection queue? Project developers seeking to connect to the grid are required by utilities and regional grid operators (RTOs) or Independent System Operators (ISOs) to undergo a series of studies before they can build their facilities, and completing the requisite grid studies is only one of many steps in the development process. Projects must also have agreements with landowners, communities, power customers, and equipment suppliers, as well as demonstrating financial readiness.

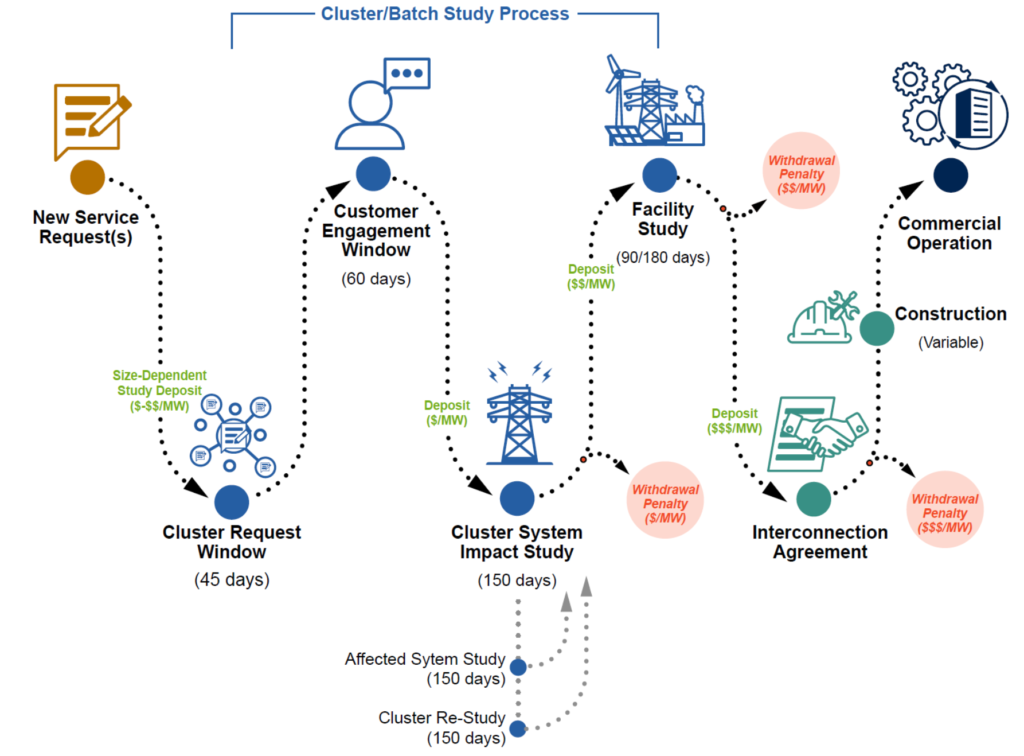

Image courtesy of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

This has major implications for transitioning the grid to renewable energy. In 2008, wait times for interconnection approval were around two years; by 2023, that delay had expanded to nearly five years. That has a serious impact on the 12,000 projects and the nearly 2,600 gigawatts (GW) of generation and storage capacity actively seeking interconnection. The total capacity in the queue at the end of 2023, nearly 2.6 Terawatts (TW), is more than twice the current U.S. generating capacity of 1.28 TW, and roughly eight times larger than the queue in 2014.

So What Are We Doing About It?

Order 2023 is the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s (FERC) new rule to address the delays in the interconnection processes.

Some of the key changes in the interconnection process include:

Previously, transmission providers studied requests to interconnect in series, one after another, as they were submitted, in a “first-come, first-served” process. The new rule will require transmission providers to study projects in batches or “clusters”. Rather than “first come first served” the priority has been changed to “first ready, first served”.

In order to increase the speed of interconnection processing, the rule imposes firm deadlines and penalties if transmission providers fail to complete interconnection studies on time. In the past, providers were only required to show that they had made a “reasonable effort” to comply with deadlines.

The Order also imposes stricter financial readiness and “site control” requirements for interconnection customers. Site control means showing evidence that the interconnection customer has the right to develop the land or site where its generating facility will be built.

As a result of these reforms, interconnection queues will be shortened by including only projects likely to be built. Previous interconnection practices allowed interconnection customers to proceed through the process without having to prove that they had the resources to complete a project. When projects withdraw their application or fail to complete, the entire queue is delayed.

The rule also allows hybrid technologies, such as solar paired with battery storage, to share an interconnection point.

In addition, transmission providers must consider alternative transmission technologies (ATTs) when conducting a cluster study, which can be deployed faster and at lower costs than traditional network upgrades. Examples of ATTs include advanced conductors, advanced power flow control, transmission switching, voltage source converters, static synchronous compensators, static VAR compensators, synchronous condensers, and tower lifting.

What’s Next?

Although Order 2023 should create some marked improvements in the interconnection process, it’s just a step in the much longer process of upgrading the grid for the coming explosion of demand for more electrical power from EVs, data centers (including AI and crypto), new building construction, and manufacturing. Next will come a new rule on transmission planning, and perhaps the most critical issue to be addressed: interregional transmission. Grid reliability will require the ability to share power between regions of the country as spikes in power demand become more common due to increased climate volatility and the electrification of infrastructure, transportation, and industry.

References:

Utility Dive: FERC Order 2023 won’t solve fundamental interconnection problems

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory: Characteristics of Power Plants Seeking Transmission Interconnection As of the End of 2022 (pdf)

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory: Grid connection backlog grows by 30% in 2023, dominated by requests for solar, wind, and energy storage

Federal Energy Regulatory Commission: Explainer on the Interconnection Final Rule